Things I Like: Connections with James Burke

There is a thing called “channel drift”. It is a phenomenon where a particular station or network starts out with a theme, a stated purpose and slowly over time drifts away from that and becomes something else entirely.

It’s like when your favorite classic rock station starts throwing Top 40 into the mix and before you know it they are playing nothing but pop music with an occasional flashback Sunday. Or say, a channel devoted to history that begins to claim that everything was caused by aliens and that pawn shops are somehow museums. It is an unfortunate trend and there are many examples.

The most egregious, in my opinion, is TLC. TLC once stood for The Learning Channel. Now it stands for … actually I don’t know what it stands for now. If it still stands for The Learning Channel then it must be meant ironically or needs to be said while holding back muffled laughter. It is now a haven for the most base and vile sort of “reality” programming. Misbehaving children and obnoxious man-boys and screaming brides are the subjects of some of the “best” shows it has to offer. No, there is no longer any learning on The Learning Channel. Unless of course it’s learning how to be a horrible, horrible person.

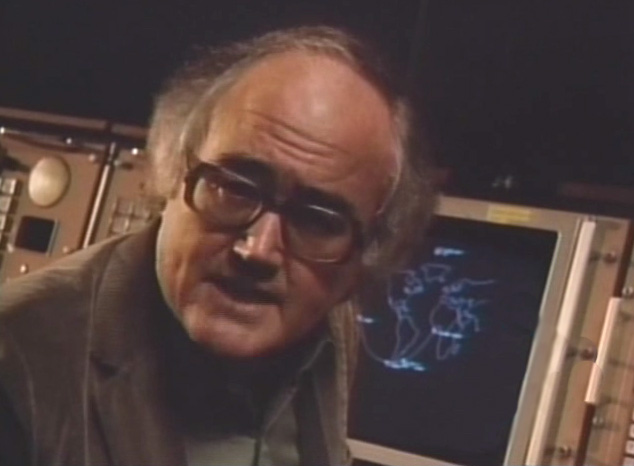

But once upon a time TLC was dedicated to educational programming. It was a destination for inspirational and enlightening and (for me at least) damned entertaining TV. And the one program I enjoyed the most and remember with great fondness was Connections with James Burke.

Connections was a documentary series produced by the BBC and distributed in the US by PBS originally and then later TLC. Subtitled an Alternative View of Change the series was the brainchild of writer, historian and presenter James Burke. Each episode Burke would follow a trail of ideas and inventions and discoveries from ancient history (sometimes as far back as the Stone Age) to the present day. Along the way he made the connections – get it? – that led from, say, the invention of agriculture to the invention of the automobile. The programs invited you to think in different ways. To see the world as not just a series of unrelated moments in time but as an interconnected whole; each person, idea and invention affecting each other is ways that were not intended but that in hindsight seem self-evident. A non-liner gestalt of history.

An example: The invention of the movie projector.

Castle fortifications are caused by the invention of the cannon. The use of the cannon caused changes in castle fortifications to eliminate a blind spot where cannon fire could not reach. This improvement in castle defence caused innovation in offensive cannon fire, which eventually required maps. A need arose to view and map locations (like a mountain top) from a long distance, which led to the invention of limelight light source, and later the incandescent light.

Next we move on to film. Film is made with celluloid (made with guncotton) which was first invented as a substitute for ivory in billiard balls.

Then came the invention of the zoopraxiscope which was first used for a bet to see if a horse’s hooves all left the ground at any point while galloping. The zoopraxiscope used frame by frame pictures and holes on the side to allow the machine to pull the film forward.

Communication signals for railways using Morse’s telegraph led to Edison discovering how to speak into a microphone creating bumps on a disc that could be played back—the record player. This gave movies sound.

Summary: Burke connects the invention of the movie projector to four major innovations in history: the incandescent light; the discovery of celluloid; the projector that uses frame by frame pictures on celluloid; and finally, recorded sound.

–Connections, 1978, episode 9

Connecting the Connections

Connections started its first run in 1978. It was an immediate and critical success – in Britain. The show wouldn’t make its way to the US till the mid-80s, and even then only in limited circulation. Burke then did a companion series called The Day the Universe Changed. It followed the same format but emphasized the philosophical side of things rather than the science; although there were plenty of both in each series. Each show had episodes that ran just under an hour and usually had a basic theme that it followed rather than a particular invention.

That would change in 1993 when a second Connections series was produced; by then being aired on TLC (this is where I come in). Called Connections2, the show was cut down to 30 minutes and was tighter and quicker and focused more exclusively on and particular invention – the car, the airplane, the computer. It didn’t linger on the details the way the previous series did and if you weren’t paying attention you might miss link in the chain. This did not effect my enjoyment in the least. I loved it. And it was popular. TLC began playing reruns of The Day the Universe Changed and the original from the 70s. I went and bought all three on VHS to watch over and over again because well, I do that sort of thing. And there was a companion book that was written like a “make your own adventure” book; allowing you to skip around making your own connections. And in 1997 a third series, Connections3, aired on TLC and again became popular and highly rated (for basic cable you understand).

Because of the years between series there is a distinct change in the appearance and production values. The huge banks of computers and the rotary phones in the 70s, the feathered hair and the emphasis on the amazing micro-chip in the 80s and the slicker faster pace for the 90s. All of this I personally find charming and fascinating to watch again now. In the 70s incarnation Burke wears a brown, polyester suit throughout with a collar that one could hang-glide with, something I could totally picture a hipster in Brooklyn wearing now. Ironically of course.

If I have a criticism of the show it’s that it is very western-centric. Burke is after all an English historian. Most of the thoughts and ideas are distinctly European and tend toward the Greco-Roman ideal of rationalism and Enlightenment thinking. To be fair Burke does delve into Eastern and Mid-Eastern thought from time to time but mostly stays close to the Western ideal.

I think this can be forgiven though. It is never done in a malicious or superior way. And Burke’s easy, engaging presentation style completely draws you in. He is energetic and funny, at times downright cynical but always entertaining. He balances a hopeful view of the world and of history with a serious warning about the threats of certain ideas and trends and where they might lead. The notion, for instance, that the rise of technology and our dependence on it might lead to individuals voluntarily abandoning their privacy to the whims of corporations and governments. I scoffed at that at the time. No one would do that.

And, Burke warned, that the proliferation of more and more outlets of entertainment might lead to a watering down of content. A drift from the ideal, the goal, the stated purpose.

The connections are there, we just have to see them.

Andy Garcia says:

Joe says:

Paul Matthew Carr says: