Guest Post: Bohemian Rain

A Guest Post from David Hicks

My father is long gone, having died in January 2007, and at first he seemed to hang around—at the foot of my bed, threatening to twist my toe to wake me up; across from me at my desk, telling me I might be working too hard; or in my dreams, as angelic as anyone could manage to be in baggy jeans and a sweatshirt—as he always was, the father I knew, scrutinizing, wondering, observing. He had something to tell me, something parental, something he hadn’t written down in the notes he had left to his loved ones in a sealed envelope in the attic.

After a while, he disappeared from my surroundings and moved into my dreams, not as the stressed, overworked, hard-to-hug man of my youth, but the still-overworked-but-more easygoing father of my adulthood, the man whose happy voice (“Dav!”) greeted me on the phone or whose hand on the back of my head, wordlessly signaling my need for a haircut, conveyed his love. He seemed to enjoy playing a cameo role, silent and supportive, along for the ride, whether the dream was anxious or fun-loving. Not my actual father but a more benign and supportive version, hovering at the periphery, there if I needed him, with his kind eyes and thin smile. Closer to the father I knew when he was in his early seventies, before he died.

But then he started popping up in public, in the faces of strangers. At Coors Field in Denver they employ retirees as greeters, and when I entered the stadium with a friend one of them looked me in the eye and said, “Enjoy the game, son.” And when I left, the same man shyly put his hand up for a high-five and said, “How about that Charlie Blackmon, huh?” in the same tone that my father would have used on the phone after he watched a basketball game: “Did you see Carmelo tonight? What a shot at the end! Love that kid’s smile—he really enjoys playing the game, doesn’t he?”

This kept happening—not all the time, but every few months or so: I saw him in the slumped, helpful posture of a security guard; in the food-delivery man’s careful manner as he handed me my order; in the ticket-taker’s welcome at a museum. Like my father, these men were all (a) tired, (b) pouchy-faced; (c) soft-spoken, and (d) happy to be of service.

I’m in Prague right now, on a Fulbright scholarship, and the other day I was on a bus with other scholars and commissioners, traveling from a village called Liblice, where we were enjoying a three-day conference, to an old brewery in Lobeč. As I entered the bus, I noticed something familiar about the driver, but I sat a few rows back and didn’t think much about it after that. It had been a gray day and now the rain was falling, and it continued to fall for the rest of the drive, and during the brewery tour as well, and rain, especially a soft rain, has a way of inviting memories. And so as we drank some delicious beer, ate a sumptuous dinner, and toured the facilities, my father kept swimming in and out of my consciousness. In fact, I remember using that word, swimming, in my mind—Hey Pop, what are you doing, swimming around in my brain? Do you have something to tell me?—an appropriate metaphor, I guess, since he was an excellent swimmer, a lifeguard in his youth. And that led me into a half-reverie, half-memory, while standing in the rain outside the brewery walls, about a day at the beach when I was a boy: my brother and I were tossing a ball back and forth in the surf, and I was swimming out deep to retrieve a ball I had missed, but the ball kept drifting into deeper water and then suddenly I was ensnared by a riptide, and the lifeguard’s whistle was blowing and a motorboat was coming after me but then there was my dad—how he had arrived first I’ll never know—grabbing me from behind, yelling at me to forget the damned ball, and pulling me back to safety.

I’m in Prague right now, on a Fulbright scholarship, and the other day I was on a bus with other scholars and commissioners, traveling from a village called Liblice, where we were enjoying a three-day conference, to an old brewery in Lobeč. As I entered the bus, I noticed something familiar about the driver, but I sat a few rows back and didn’t think much about it after that. It had been a gray day and now the rain was falling, and it continued to fall for the rest of the drive, and during the brewery tour as well, and rain, especially a soft rain, has a way of inviting memories. And so as we drank some delicious beer, ate a sumptuous dinner, and toured the facilities, my father kept swimming in and out of my consciousness. In fact, I remember using that word, swimming, in my mind—Hey Pop, what are you doing, swimming around in my brain? Do you have something to tell me?—an appropriate metaphor, I guess, since he was an excellent swimmer, a lifeguard in his youth. And that led me into a half-reverie, half-memory, while standing in the rain outside the brewery walls, about a day at the beach when I was a boy: my brother and I were tossing a ball back and forth in the surf, and I was swimming out deep to retrieve a ball I had missed, but the ball kept drifting into deeper water and then suddenly I was ensnared by a riptide, and the lifeguard’s whistle was blowing and a motorboat was coming after me but then there was my dad—how he had arrived first I’ll never know—grabbing me from behind, yelling at me to forget the damned ball, and pulling me back to safety.

And then my mind was swimming, and I was looking up at the sky outside the brewery and I couldn’t hear anything the tour guide was saying and all I knew was that I was in the dark twilight of Bohemia and it was raining harder now and my dear father, the best swimmer I have ever known, has been dead for fifteen long years.

By the time we all climbed back into the bus for our return trip, the sky had darkened, and the rain had settled into a light drizzle. I sat in the front row this time, to the right of the driver, as he nodded kindly to everyone as they entered, as if to tell us he was aware we had all been drinking beer, but he had been in the bus the entire time, had exited only to smoke a cigarette, and he would now be delivering us safely back to Liblice. He started the engine, sat patiently until everyone was settled and the road was clear, then steered the large bus down the wet, narrow, country roads of Bohemia.

I kept watching the wet windshield, the wide wipers rhythmically swiping from edge to center, from edge to center, until finally I gathered the courage to look at him.

It’s not so much that he resembled my father—he did, but just a little—but that he felt like him—as in, If Dad were a bus driver, this is the bus driver he would be. My father had spent much of his life in service of others—his children and grandchildren mostly, but as a deli owner he enjoyed making extra-big sandwiches for his regulars, and as a security guard, stationed in one of those little shacks at the entrance to a gated community, he happily did favors for the residents, giving them a friendly wave as they entered and exited. He was the kind of person who enjoyed helping others to get where they wanted to go.

This, I suppose, is how the dead stay with us. First in our rooms, then in our dreams—always in our dreams—but also through others. Have you not even thought of me lately? Well surprise, here I am.

We are all the dead and the dead are in all of us.

What is it he wanted to tell me, hovering in the room with me like that, in the weeks after his death? I have no idea. Quit worrying so much. Give Cynthia a kiss. Hey, go easy on the kids. Write another book.

Or maybe it was what he had such a hard time saying his whole life: Son. I love you with all my heart.

As I approach the age my father was when he died, I can only hope that I will, in a manner of speaking, become him, or become a dream of him while still alive, a living, swimming reverie of the man I love.

Until then, I am adrift in some unconscious riptide of mythic destiny, helplessly but willingly surrendering to the inevitable. I am in the ocean, the whole world sparkling in sunshine, and I am clutching his strong shoulders as he bobs in and out of the saltwater, making dolphin sounds, and then my hands are empty, and I’m adrift, and a soft rain is falling and I’m drowning, but then he’s there again, he’s there underneath me, behind me, alongside me, and I swim, alone but not alone, and I gulp the air, but I’m okay.

He is gone, and I am lost. He is never gone, and I will never be lost.

He lives on in me. I’ve long known that he lives on through my mother, who quotes him all the time; and in my soft-spoken, kindhearted brother; and in my sister, who has worked as a teacher, helping others, her whole life; and in his beloved grandchildren, in whose personalities I see his many influences. But what I am just now realizing is that he lives on in me.

And through others as well, even in strangers, even in the Czech Republic of all places—in the eyes and postures of all the men in their seventies, here and everywhere, who are quietly going about their business, self-effacing and kind, driving people safely home through the rain.

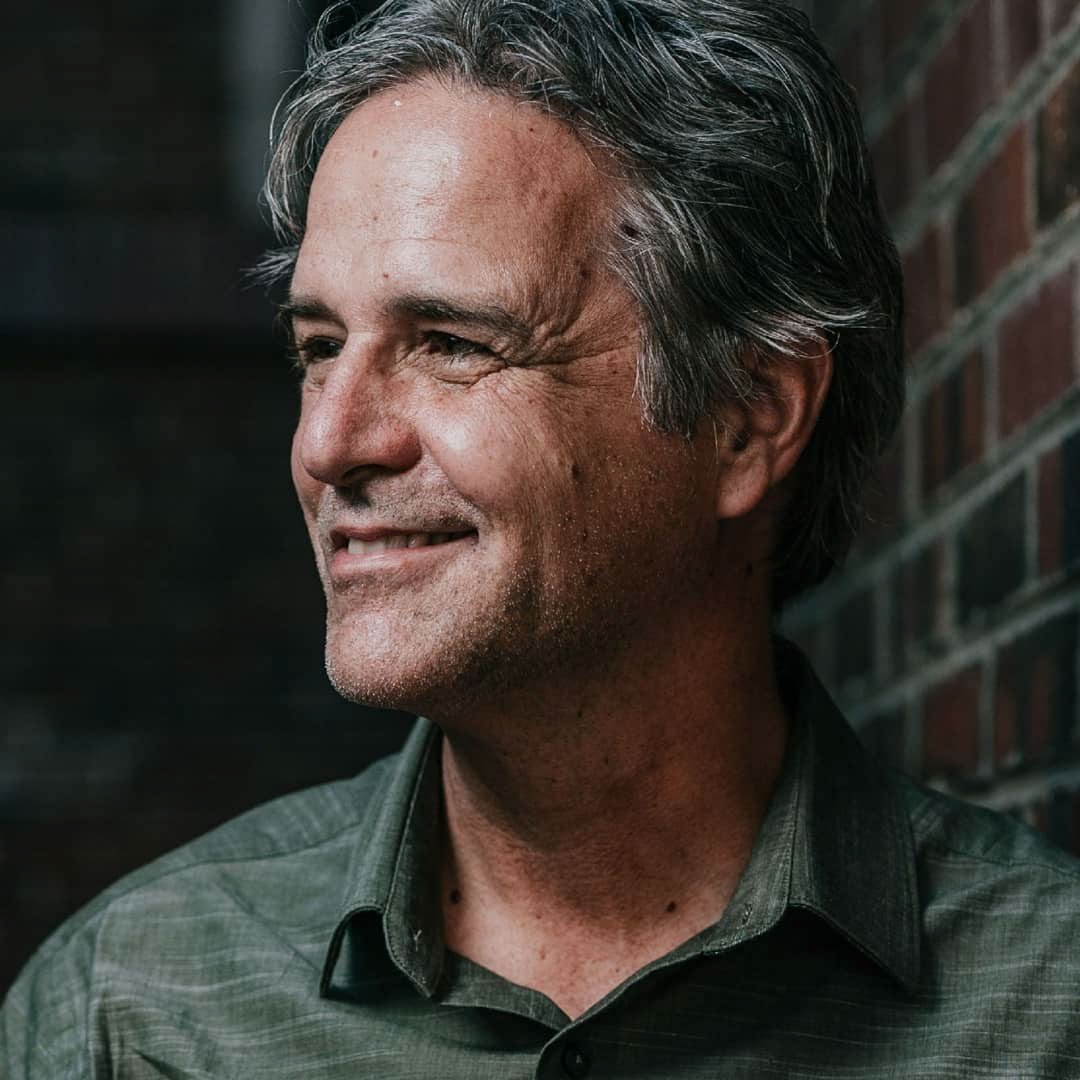

About the Author: David Hicks

David is the author of the debut novel, White Plains, published by Conundrum Press in 2017, and a finalist for the Colorado Book Awards (2018). Excerpts from the novel have been published as short stories in Glimmer Train, Colorado Review, Specs, Saranac Review, and South Dakota Review, along with other stellar journals. More of David’s writing can be found on his website david-hicks.com

Likhon chowdhury says:

Conor says:

Andy Garcia says: